Jorge Molder – Jeu de 54 Cartes

Jorge Molder

27/Oct/2017

- 28/Jan/2018

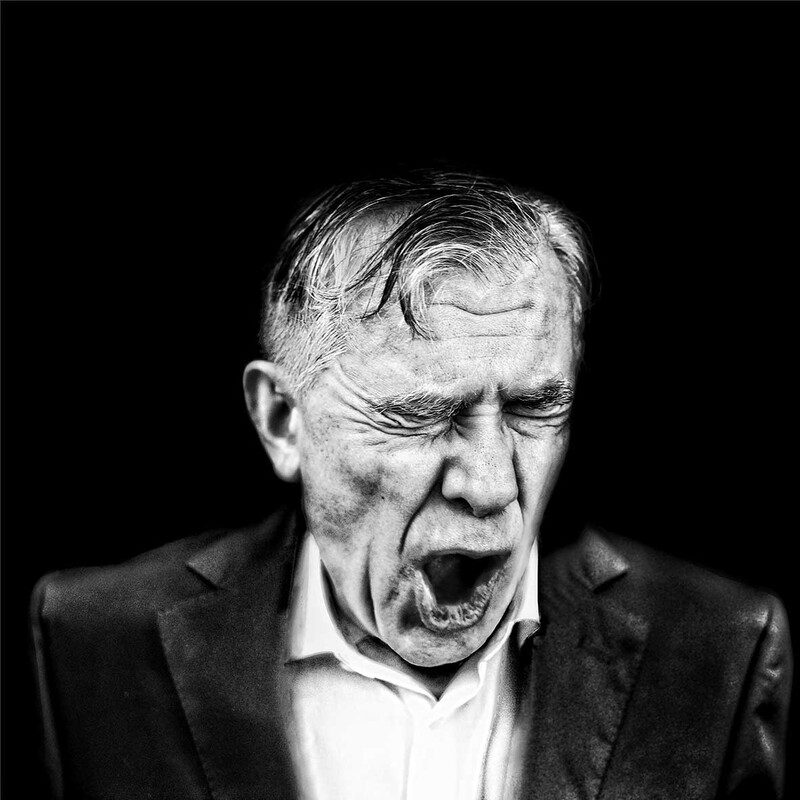

Since the late 1970s, Jorge Molder has been exploring the possible variations and intersections between self-portrait and self-representation, as a peculiar and fertile domain in investigating the multiple and unpredictable connections between the perceptibility of appearances and the intricacies of the experience of imagination. In many of the series he has produced, we are continuously confronted with the presence of the artist, who reveals his face and its expressions, gestures, and body movements. Nonetheless, what we see is the model presence of an indistinct and generic figure, with a minimal set of characteristics, a figure that mediates several figures, roles, visages, and substitutes—the protagonist of a game designed to reconfigure our understanding of the differences and overlaps between the ideas of authenticity and dissimulation, reality and fiction, physical body and body-image.

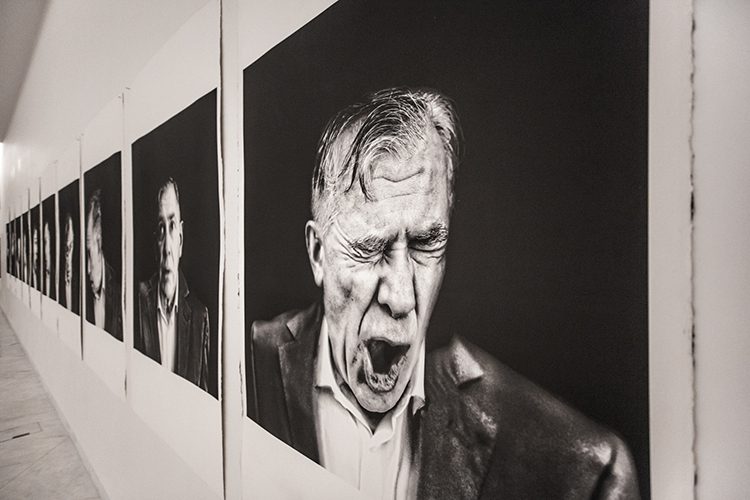

This exhibition presents Jorge Molder’s most recent series, Jeu de 54 cartes, created over the current year. Based on the typical structure of the popular French playing card deck, consisting of four suits of thirteen cards each, the artist produced a series of photographs with six parts: fifty-two images divided into four suits (Faces, Hands, Bites, Specters), plus two Jokers and a photograph of a Template.

The notion of play is an essential element in Jorge Molder’s creative process. Play emerges as an activity that invites us to a heuristic experience of things, enabling openness to everything that deviates from conventions, categories, and pre-established structures of understanding. Applied to the field of art, it is a notion that certifies art as a practice that formulates its own “rules,” the possibility of setting aside deliberate intention, systematization, and prior discourse in favor of the experience of possibility, spontaneity, and interpretative availability.

Play, and correspondingly, chance and intuition, point to decisive questions in this inquiry where Jorge Molder correlates the work of multiplying (his) figures with the essential dilemmas of our relationship with images. Now, if images seem to refuse the expectation of a unique and original Self, first and authentic—because each individual is also constituted by their declinations and substitutes—they simultaneously alert us to the paradoxical nature of the relationship between the image and each figure it presents. What is true and what is artificial in that body, in that gesture, in that expression? How can we distinguish what separates and what juxtaposes image and representation, reality and fantasy, the Self and the other(s)?

Exhibition